Introduction

Canada is confronting a youth employment crisis of a magnitude not seen in a generation. As of mid-2025, the labour market for young Canadians is defined by historically high unemployment, declining workforce participation, and deepening precarity. Canada has had one of the sharpest increases in youth unemployment among major advanced economies in recent years. This situation, however, is not a simple cyclical downturn that can be weathered or addressed with short-term stimulus. It is the manifestation of powerful new economic forces colliding with the nation's oldest and most enduring structural realities. To understand why a young person in Alberta faces a fundamentally different job market from their counterpart in Quebec, and why national solutions invariably become mired in federal-provincial conflict, one must first understand the historical foundations upon which the modern Canadian economy was built.

The Staple Economy

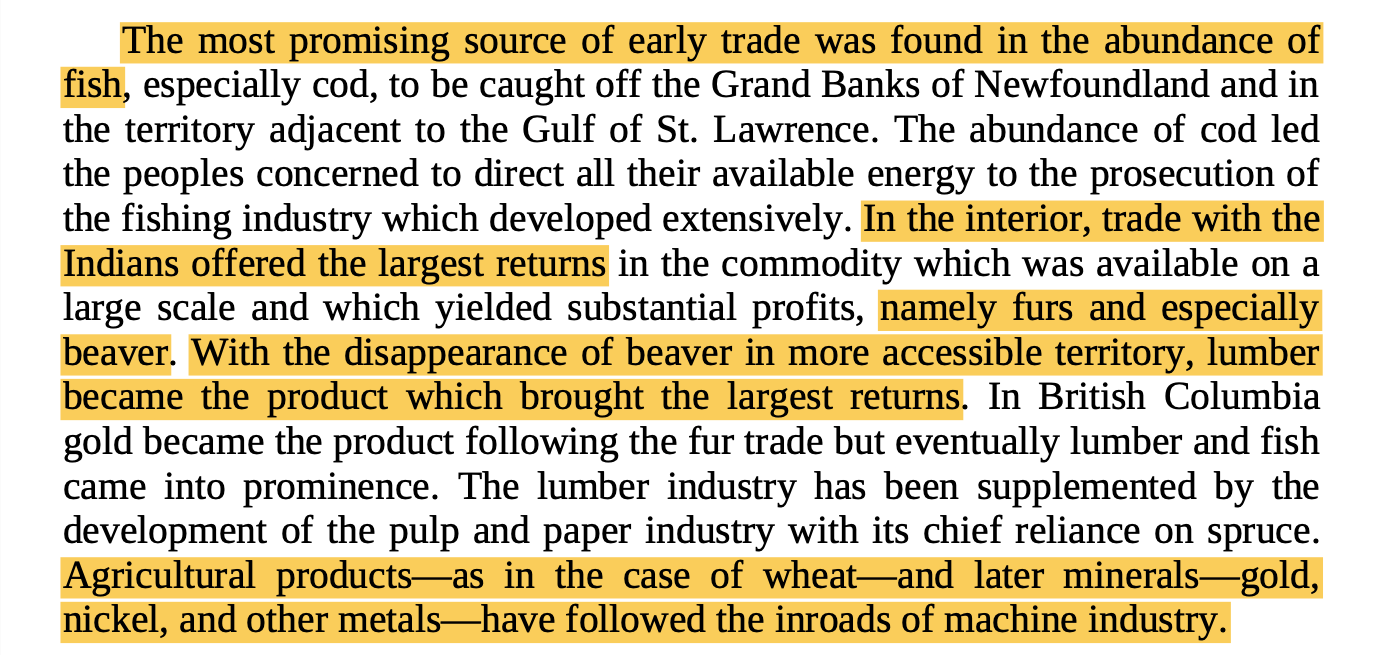

The economic and political structure of Canada is the product of a persistent historical tension between the centrifugal forces of a resource-based, regionally fragmented economy and the centripetal forces of a centralized political and financial apparatus designed to manage it. This dynamic was first identified in the study of the nation's earliest commercial activity through the Staples Thesis1.

As political economist Harold Innis argued, Canada’s evolution was shaped by the search for and exploitation of a succession of staple commodities—raw materials like fur, timber, and wheat, exported to imperial metropoles. This economic model had profound and lasting consequences. Different staples, with their unique geographical and production requirements, created distinct regional economies and, by extension, distinct regional societies and political cultures.

The centralized, corporate fur trade fostered a different society in Central Canada than the decentralized cod fishery of the Atlantic or the independent, individualistic wheat farming of the Prairies. This history established a lasting pattern of powerful, regionally-specific economic interests.2

Canadian federalism was conceived to provide the political architecture to manage these differences. The country's foundational constitutional document, the Constitution Act of 1867, embeds the potential for economic conflict by granting the federal government broad powers over the national economy while giving the provinces exclusive jurisdiction over property, civil rights, and the management of natural resources.3

This design ensures that nearly any major national economic policy or large-scale resource development project will inevitably create jurisdictional friction. As a result, Canada’s history is a continuous narrative of attempts by a centralizing state to forge a national economy, with each attempt—from Sir John A. Macdonald's National Policy to Pierre Trudeau's National Energy Program—reigniting the fundamental tensions between the industrial centre and the resource-producing peripheries.4

I am a big believer in analysis of long durée, and this historical framework is the essential context for the crisis of 2025.5 The sharp regional disparities in youth unemployment—with rates reaching over 17% in an Alberta facing trade headwinds while remaining comparatively lower elsewhere—are a modern echo of these deep-rooted economic fault lines. The intense federal-provincial battles over the policy response, from labour market regulation to infrastructure spending and immigration levels, are a continuation of the same conflicts over wealth, jurisdiction, and economic control that have defined the federation since its inception.

This historical structure is now being stressed by a new set of powerful global tectonic forces. The most significant factor of our era is the aging population and a reliance on mass migration as a bandaid for all Western states; rapid technological change driven by artificial intelligence/automation is disrupting industries; unprecedented levels of public and household debt constrain policy options; and the climate transition is forcing a fundamental re-engineering of the nation’s resource-based economy.6

Canada’s youth employment crisis is the primary symptom of this collision between the 21st century’s global pressures and the 19th century’s institutional design. It is the result of modern structural failures—in housing, market competition, immigration policy, skills development—that are being amplified by Canada’s historical path dependency. Politicians and technocrats will get bogged down in unimpressive short-term cyclical analyses. Only a comprehensive survey of the deep-seated structural and historical roots of Canada’s economic malaise give us a clear picture. This report is meant to be diagnostic. It will proceed by first defining the dimensions of the crisis, then dissecting its structural causes, and briefly evaluating the performance of current policy interventions.

Youth Unemployment

The Immediate Catalyst: The Q2 2025 Economic Downturn

The youth employment crisis of mid-2025 emerged from an immediate economic downturn that laid bare deep structural fragilities that had been simmering beneath the surface of the Canadian economy. An examination of Canada’s macroeconomic performance in the first half of the year reveals a narrative of two conflicting quarters: the first presenting a facade of robust growth, immediately followed by a reversal in the second that laid bare the underlying weaknesses in the critical goods-producing sectors. This downturn acted as the catalyst, translating long-standing labour market challenges into an acute crisis for young Canadians.

The Deceptive Strength of Q1 2025

On the surface, the Canadian economy began 2025 on solid footing. Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increased by 0.5% in the first quarter, an annualized growth rate of 2.2% that would normally suggest a healthy economy7. However, a deeper analysis reveals this growth was not built on strong domestic fundamentals. Instead, the expansion was overwhelmingly propped up by a temporary surge in exports and inventories.

The primary driver was a 1.6% increase in exports, concentrated in sectors like passenger vehicles (+16.7%) and industrial machinery (+12.0%). This activity was not a reflection of surging global demand but a direct reaction to the external political environment, as businesses front-loaded exports to get ahead of looming U.S. tariffs. This statistical distortion masked significant weakness in core domestic activity. Household spending growth slowed dramatically to just 0.3%, while residential investment fell by 2.8%, driven by a collapse in housing resale activity.

The Q2 Reversal and Sectoral Contraction

The artificial strength of the first quarter proved fleeting. As anticipated trade disruptions materialized, real GDP edged down by 0.1% in April 2025, with advance estimates indicating another 0.1% decrease in May. This signalled a high probability of economic contraction for the second quarter as a whole.

The downturn was concentrated in the trade-exposed goods-producing sectors of the economy, which are major employers. Key sectors that drove the decline include:

Manufacturing: This sector contracted by a steep 1.9% in April—its largest single-month drop since April 2021. The transportation equipment subsector plummeted 3.7% as motor vehicle manufacturing was scaled back in direct response to tariff uncertainty.

Wholesale Trade: This sector contracted by 1.9%, its largest decline since June 2023, again linked to a sharp drop in the motor vehicle and parts subsector.

This causal chain is clear: the anticipation and implementation of U.S. tariffs led directly to the growth mirage of Q1, only to be followed by the Q2 slowdown as trade collapsed and manufacturing output contracted. This manufacturing downturn, concentrated in industrial provinces like Ontario, is a primary driver of the loosening labour market and falling job vacancies that have disproportionately impacted young people seeking to enter the workforce. The economic slowdown acted as the trigger that exposed the pre-existing structural barriers facing youth, turning a challenging situation into a full-blown crisis.

The 2025 Labour Market Snapshot

To get a feel for the severity of the youth employment situation in Canada, it is essential to establish a clear empirical foundation. The data from the first half of 2025 paint a stark picture of a labour market in significant distress, characterized by high unemployment, declining participation, and widening regional disparities. This section moves from the national aggregate to provincial and demographic specifics to illustrate the depth and breadth of the crisis.

National Unemployment Landscape

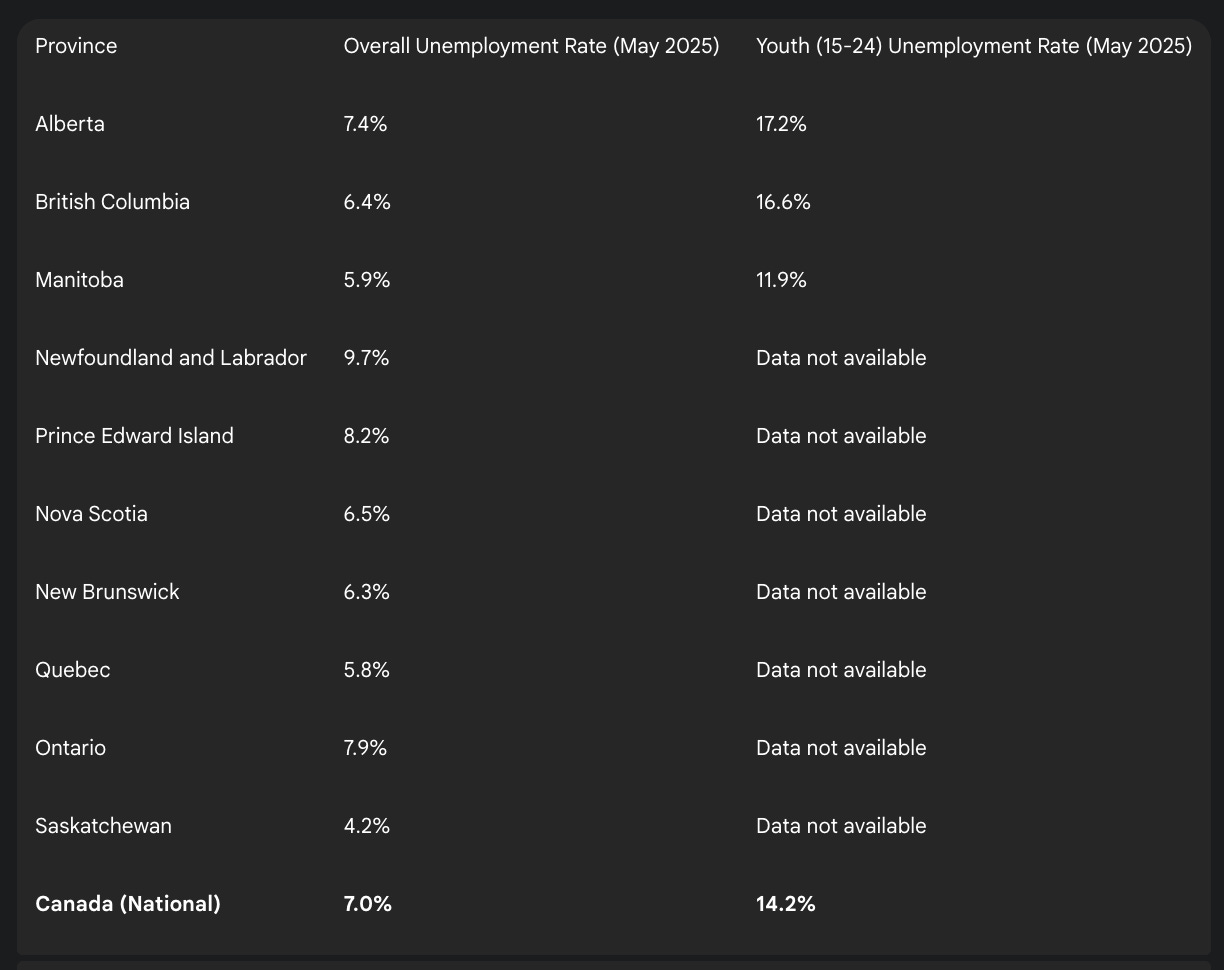

The Canadian youth labour market is demonstrating clear signs of systemic weakness. The seasonally adjusted unemployment rate for youth aged 15 to 24 reached 14.2% in May 2025.8 This figure represents a significant deterioration from the 12.8% recorded one year prior and marks the highest level of youth unemployment since the mid-1990s, excluding the anomalous period of the COVID-19 pandemic. The rate is more than double the overall national unemployment rate, which itself climbed to 7.0% in May, its highest point since 2016.

This is not a sudden development but the culmination of a sustained negative trend. The youth unemployment rate has been climbing steadily, from 10.9% in January 2024 to 13.6% in January 2025, before reaching its current peak. The current rate now exceeds the long-term average of 13.89%, signalling a significant and troubling deviation from the historical norm. This persistent increase over the last 18 to 24 months points to structural issues rather than temporary, cyclical fluctuations.

The Provincial Fault Lines: An Uneven Crisis

The national average, while alarming, conceals severe regional disparities that underscore the uneven nature of the crisis. The burden of youth joblessness is not shared equally across the country, with several provinces experiencing conditions far worse than the national aggregate.

Alberta and British Columbia have emerged as epicentres of the crisis. In May 2025, Alberta recorded a youth unemployment rate of 17.2%, the highest in the nation, while British Columbia followed closely at 16.6%. These figures are substantially higher than their overall provincial unemployment rates of 7.4% and 6.4%, respectively, highlighting the disproportionate impact on their youngest workers.

In contrast, other provinces exhibit more stable labour markets, though youth still face challenges. Manitoba’s youth unemployment rate stood at 11.9% in May 2025, which, while lower than in Alberta or B.C., represented a significant monthly increase of 1.6 percentage points. While we don’t have the data on youth unemployment rates yet, provinces like Saskatchewan and Quebec reported much lower overall unemployment rates of 4.2% and 5.8% respectively, suggesting as we’d expect from our historical survey that regional economic structures and industry compositions play a crucial role in labour market outcomes. Ontario, Canada's most populous province, registered an overall unemployment rate of 7.9%, a high figure that significantly influences the national average.

Indicators of Deepening Precarity

The headline unemployment rate, while critical, only captures part of the story. A wider lens reveals multiple indicators of a deteriorating labour market for young people, characterized by declining participation, insecure work, and increasing difficulty in finding any employment at all.

The youth employment rate—the proportion of the youth population that is employed—stood at 54.1% in May 2025. This figure is down 1.1 percentage points on a year-over-year basis, indicating that a smaller share of young people are successfully securing work. This represents the lowest youth employment rate since 1999, excluding the pandemic years, signalling a long-term erosion of labour market attachment.

The situation is particularly dire for students. The summer job market, a critical period for gaining income and initial work experience, has effectively collapsed for many. In May 2025, the unemployment rate among returning students aged 15 to 24 was a staggering 20.1%, a sharp increase of 3.2 percentage points from May 2024.

Furthermore, the nature of the jobs available is increasingly precarious. Statistics Canada analysis from May 2025 shows that a smaller share of unemployed individuals are successfully transitioning into employment compared to both the previous year and pre-pandemic averages. Consequently, the average duration of unemployment has lengthened. Most alarmingly, nearly half (46.5%) of all unemployed people in May 2025 had either never worked or had not worked in the past 12 months, a significant increase from 40.7% a year prior. This points to a growing cohort of youth who are entirely disconnected from the labour market, unable to secure even a first job.

The Structural Roots of Youth Joblessness

The Four Drivers of the Crisis

The current crisis in youth employment cannot be attributed solely to cyclical economic headwinds. It is the manifestation of deep, long-term structural transformations in the Canadian economy that have systematically eroded the stability and accessibility of entry-level work. These drivers are not independent phenomena but constitute a self-reinforcing system of economic fragility and social inequality. This system generates a cycle of debt-fueled, low-productivity growth that systematically disadvantages younger generations, erodes the quality of employment, and constrains the nation's long-term prosperity. This chapter dissects the four primary structural drivers of the crisis.

A: The Financialization of Housing

At the heart of Canada’s contemporary economic challenges lies the transformation of housing from its social function as housing into a vehicle for financial speculation. This process, known as the financialization of housing, involves the growing dominance of financial actors—such as Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) and private equity firms—in the ownership and management of residential property.

In Canada, REITs grew from owning zero rental suites in 1996, to nearly 200,000 last year, and financial firms hold 20–30% of the country’s purpose-built rental housing stock.9

This concentration of capital in urban real estate is a modern manifestation of a historical pattern; the same metropolitan and financial cores in Central Canada that once marshalled the capital build the national railway and the staples trade now deploy that financial power in the housing market. These entities view housing primarily as an asset to maximize investor returns, pursuing strategies that systematically undermine affordability.

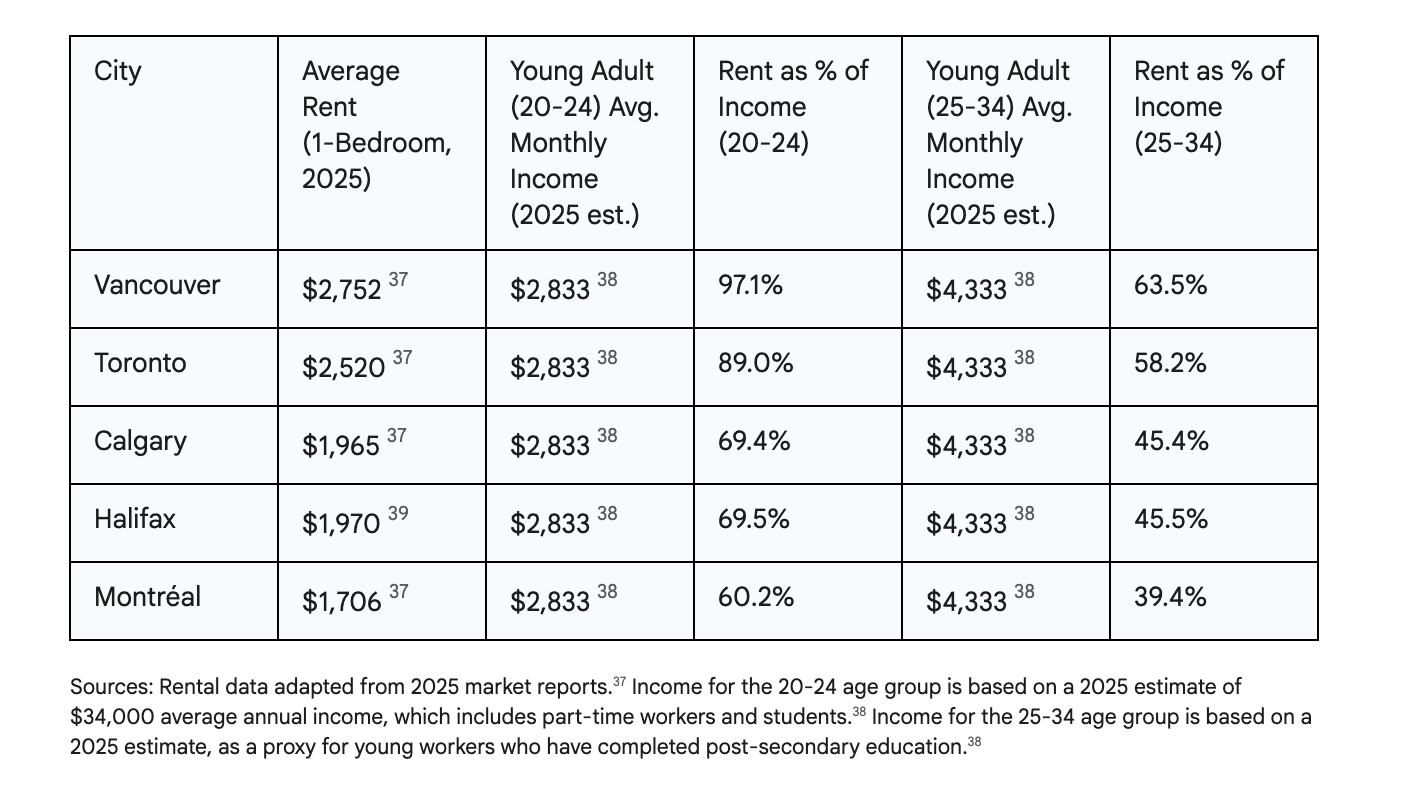

This structural prioritization of housing as a financial asset has profound consequences for the allocation of capital across the economy. The immense volume of capital flowing into residential real estate—attracted by the perception of safe, state-backed returns—comes at the direct expense of more productive, innovation-driving sectors. This “crowding out” effect is a key driver of Canada's chronic underinvestment in the machinery, technology, and R&D needed to create high-quality jobs.

These consequences reverberate through the labour market, creating an “affordability anchor” that cripples youth mobility and opportunity. The extreme cost of housing in Canada's major urban centres, the very places with the highest concentration of specialized jobs, acts as a powerful brake on labour mobility. Young people are forced to turn down career opportunities because they cannot afford to move, trapping them in regions with fewer jobs and leading to underemployment. For youth living in these expensive cities, exorbitant housing costs negate the benefits of employment. A high salary in Toronto or Vancouver has significantly less purchasing power once a large portion is dedicated to rent, diminishing the quality of life and effectively acting as a tax on wages. Saddled with student debt and facing precarious entry-level employment, the prospect of saving for a down payment has become increasingly unattainable with each passing decade. This forces them into unstable living situations, such as living with roommates or being stuck with their parents for much longer after graduating and widens the wealth gap between asset-owning older generations and a younger generation largely excluded from this primary means of wealth accumulation. The table below illustrates the structural impossibility for a young person earning a median income to secure independent housing in major job markets.

B: The Uncompetitive Landscape

The Canadian economy is defined by a pervasive lack of competition. From key sectors such as telecommunications to banking and grocery retail, markets are dominated by a small number of large, entrenched firms. This oligopolistic structure, fostered by decades of weak competition policy stifles innovation and suppresses wages. This situation demonstrates a clear path dependency; the 19th-century “National Policy” that used tariffs to protect a nascent industrial core has evolved into a 21st-century reality where a handful of “national champions” are sheltered from the vigorous competition that would force them to innovate.10

Canada’s permissive competition policy reflects longstanding tradeoffs: between competition and geographic service delivery, between market openness and economic nationalism, and between policy coherence and provincial autonomy. The result is an entrenched tolerance for market concentration that stifles innovation and suppresses wages.

Sheltered from vigorous competition, dominant firms lack the incentive to make the risky, long-term investments in R&D that drive productivity. Instead, their market power allows them to engage in rent-seeking behaviour, focusing on mergers and acquisitions rather than genuine value creation.

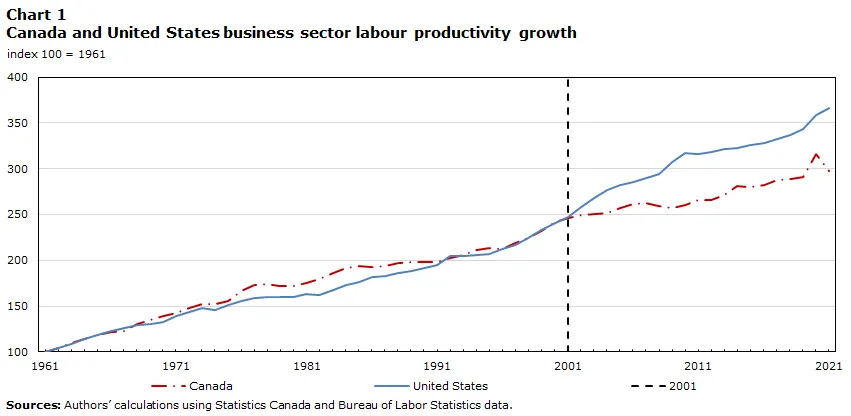

These structural weaknesses have real consequences. Canada has posted the worst per-capita GDP growth in the OECD over the last decade—just 0.5% annually—a stark illustration of its chronic productivity malaise. An economy dominated by a handful of protected incumbents often fails to deliver rising living standards or to foster internationally competitive industries outside a few resource sectors.

This uncompetitive landscape has direct and detrimental effects on the labour market for young people. In most concentrated markets, only few large firms act as the dominant buyers of labour, thus creating a large asymmetric power imbalance which weakens the bargaining position of workers, particularly new entrants. With fewer employers to choose from, firms feel much less pressure to compete for talent by offering higher wages or better benefits, contributing directly to wage erosion.

Furthermore, young innovators looking to launch a startup face nearly insurmountable barriers when trying to compete against deep-pocketed incumbents. This contributes to the “scale-up problem,” where promising Canadian startups are frequently acquired by dominant firms long before they can grow into genuine competitors, or leave to settle in the Silicon valley. This pushes young workers into stagnant sectors and risk-averse roles, choking off the emergence of new firms and cutting short serious attempts at entrepreneurship.

C: The Productivity, Wages, and Labour Market Dysfunction

For decades, Canada has struggled with a persistent productivity gap relative to its international peers, a weakness often called the “Canadian sickness.”

The primary cause is chronic underinvestment by the business sector in areas that drive innovation and efficiency, such as machinery, equipment, information technologies.11 This failure to innovate is the logical outcome of the first two drivers: capital is diverted to non-productive housing, and a lack of competition removes the incentive for incumbent firms to invest.

The New Precariat: From Standard Jobs to Systemic Insecurity

The post-war era was characterized by the Standard Employment Relationship (SER)—full-time, permanent jobs with a single employer, offering benefits and a degree of security. As documented by Jackson and Thomas in Work and Labour in Canada, this model has been progressively eroded over recent decades, replaced by a regime of precarious work. Youth are at the forefront of this transformation, disproportionately concentrated in temporary, contract, and part-time jobs that offer low pay, few or no benefits, little to no long-term security.12

This shift is a result of deliberate employer strategies, such as contracting out, franchising, and the use of a “just-in-time” workforce, which are designed to increase labour flexibility and reduce costs. For many young people this means entry into the labour market is no longer through an entry-level funnel into a stable career path, but often a churn through a series of disconnected, low-skill, insecure positions, where transferable skills or knowledge can seldom accumulate. As of 2015, nearly one-third of all young workers were employed in temporary jobs, a figure that has likely grown amidst the current market softness.

The Unpaid Internship Barrier

A particularly pernicious feature of the modern youth labour market is the rise of the unpaid internship. What is often framed as a valuable opportunity to gain experience has, in many sectors, become a mandatory yet exploitative prerequisite for entry-level employment. This ensures that only those with family wealth can afford to take unpaid roles, effectively drastically weakening social mobility for the best of the underclass.

Labour lawyer Andrew Langille estimates there are between 100,000 and 300,000 unpaid internships in Canada, describing them as a “free labour scam”, exploiting individuals and suppressing wages, as paid entry-level positions are displaced across the economy.13 The persistence of unpaid internships is also sustained by Canada’s highly concentrated industries. Dominant firms face little competitive pressure to improve wages or working conditions, as mentioned in section B. The federal Canada Labour Code provides only weak protections; student interns are afforded some rights regarding hours and breaks, the code explicitly states that employers are not required to pay them. This legal ambiguity has allowed the practice to flourish, particularly in highly cut throat competitive fields, with little oversight or consequence. It’s a clear display of employers’ leverage in a market overflowing with anxious young workers willing to take whatever they can get.

The Great Mismatch: Education, Skills, Employer Expectations

A major structural failure is the persistent gap between what Canada’s education system teaches and what employers need. Graduates often feel unprepared, while employers struggle to find candidates with practical skills. A 2024 survey found 56% of youth reporting a mismatch, describing education as too theoretical and disconnected from real-world demands.14 The COVID-19 pandemic worsened this by cancelling co-ops and internships, disrupting skills acquisition for 72% of youth—only one in five have fully recovered.

This gap is well-documented. The C.D. Howe Institute calls it a core driver of underemployment affecting over half a million workers.15 The Future Skills Centre is funding projects in AI, green construction, and digital tech to address it. Technical skills aren’t the only issue. Employers want communication, teamwork, and problem-solving, and many graduates fall short in these areas. Anecdotally, zoomers are seen as under-socialized, with reports of parents attending job interviews. In AI-related fields, 84% of youth want more training, while most educators feel unprepared to teach it.

Canada's productivity malaise translates directly into wage stagnation, insecure work, and a poor match between youth skills and employer demand. Over the long term, a country cannot pay itself more than it produces: failure to boost productive capacity is the fundamental reason why living standards for young workers have fallen behind those in peer countries.

The erosion of the Standard Employment Relationship has left youth disproportionately trapped in precarious, low-wage, short-term roles. Practices like unpaid internships, sustained by weak labour protections and a lack of competitive pressure on employers, exploit young workers and suppress social mobility. The slow pace of technological adoption creates a structural skills mismatch. Universities produce graduates with skills, but dominant, complacent firms often fail to create roles that can fully use them. It leaves grads pouring lattes or juggling contract gigs far below their training—squandering talent, widening class divides, and betting against the country’s own potential.

D: The Demographic Drag

Canada is undergoing a profound demographic transformation as the baby boomer cohort retires. In response, successive governments have turned to immigration as the primary policy tool to sustain population and labour force growth, provoking a dramatic demographic change unlike any seen in any other country, perhaps excepting the UK.

This follows a long historical tradition of using immigration as a key instrument of national economic policy; settling the Prairies for the wheat staple, filling factories after World War II, etc. However, a recent strategy of high-volume intake (an understatement) has collided with the nation's inability to build sufficient housing and infrastructure. This has abjectly been one of the worst policy-induced self-willed failures, provoking one of the world’s worst affordability crisis, forcing a rapid pivot to calls for slowing down immigration. See the charts for yourself.

The disconnect between Canada's immigration intake and infrastructure capacity has created a zero-sum battle between young Canadians and newcomers over dwindling resources. Both demographics find themselves scrambling for the same shrinking pool of affordable rental units in Toronto, Vancouver, and Montreal, where immigration policy has essentially flooded markets already starved of new housing stock. The result is rent spikes that have priced out entire cohorts of young adults while trapping newcomers in precarious living situations.

Meanwhile, the labour market tells a similar story. While an aging workforce certainly needs replenishment, the current immigration surge has flooded entry-level job markets precisely where young Canadians typically gain their footing. Add to this the mess of foreign credential recognition—where even skilled or questionably qualified newcomers end up crowding into basic roles—and you get a labour market that fails both groups while stoking resentment.

These pressures will likely get worse as the Government is aiming at making entire industries which compose the historical backbone of the Canadian economy to retool or vanish in the face of the so-called climate transition, exacerbating existing regional disparities. Some areas will scramble to adapt while others get hollowed out, deepening the existing split between thriving hubs and left-behind towns.

Policy Performance and Institutional Failures

Federal efforts amount to scattered grants and training schemes with no bite. Nothing changes the fact rents are absurd, wages are stagnant, and entire regions are drying up for lack of real investment.

Programs like the National Housing Strategy (NHS) illustrate this mismatch between crisis and policy bandaid. Launched with great fanfare, the NHS has failed to meaningfully expand affordable housing supply, with demand driven ever higher by rapid population growth. Its benchmark for “affordability” often simply tracks high market rents, leaving many young people priced out even of so-called affordable units. The result is a strategy overwhelmed by the very pressures it was supposed to mitigate.16

Similarly, labour-market programs like the Youth Employment and Skills Strategy (YESS) and Canada Summer Jobs (CSJ) focus on short-term work placements and subsidies. While evaluations find some individual benefit—CSJ participants, for example, earn measurably more years later—these programs are far too small in scale to address the true dimensions of the problem. Internal reviews note that YESS funding meets less than 20% of demand17, while Auditor General reports on CSJ highlight limited outreach, weak accountability, and the tendency to subsidize hiring that would have happened anyway.18

Overall, these federal efforts share two core failings. First, they treat youth unemployment as a problem of individual readiness rather than systemic economic structure. Wage subsidies and short-term jobs cannot fix an economy defined by weak competition, chronic underinvestment, and a housing market turned speculative. Second, they reflect a mismatch of scale. Piecemeal, localized interventions cannot offset national-level drivers like market concentration or financialized real estate. Without confronting these underlying structural failures, government policy remains a patchwork of band-aid solutions on a system in need of real reform.

Conclusion

Canada’s youth employment crisis is not a short-term downturn but the result of decades of complacency about the country’s economic foundations. A labour market defined by stagnant productivity, weak competition, precarious work, unaffordable housing, and profound demographic changes is failing its youngest workers, by design as much as by neglect.

The crisis goes beyond economics: it is precisely baked into the political structure. Canada’s model of a centralized government tasked with national trade and economic policy has always struggled to reconcile the profound diversity and mismatch of provincial economies. This tension makes coordinated solutions harder to design, negotiate, and implement, as they grow more urgent by the day.

Moreover, technological changes, especially the rapid deployment of AI tools, is likely to further transform the entry-level job market, automating many of the very positions young workers have traditionally used to gain experience and stability. Without real structural adaptation, locked out of the gateway to the middle class, these forces will probably convert younger workers into a permanent underclass, sealing their economic destiny.

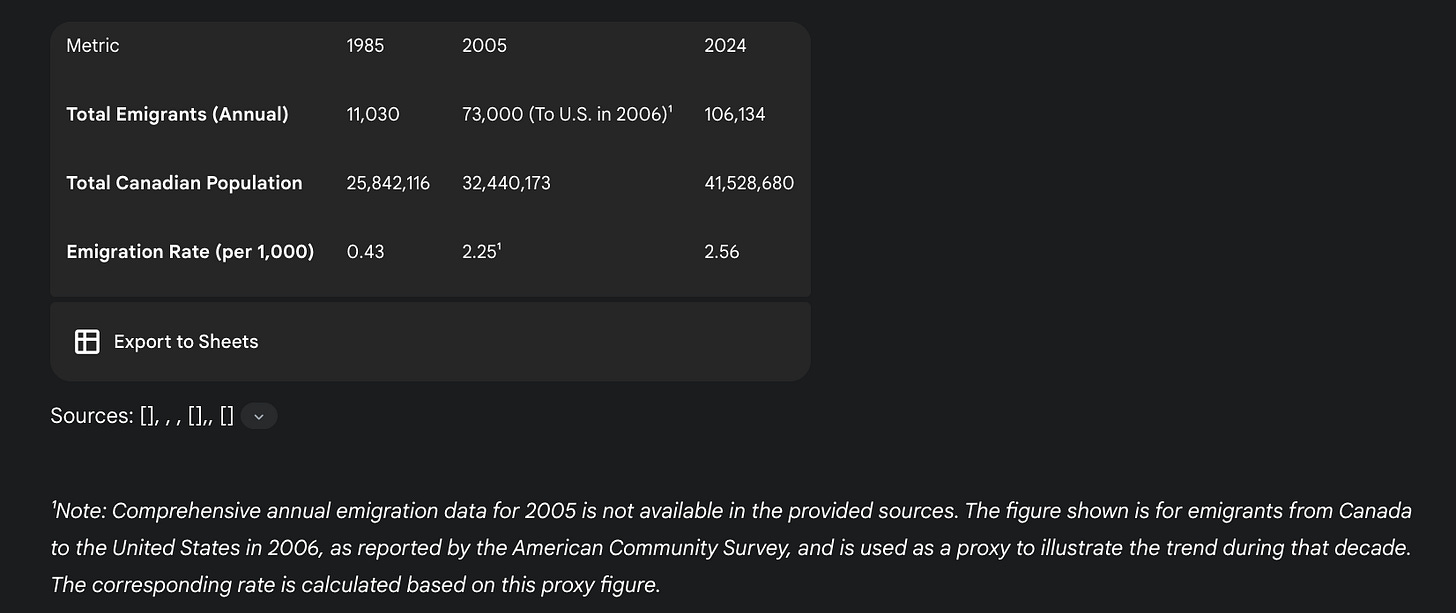

The Canadian emigration rate has been increasing, with most common destination to the US

I am not a policy wonk. I don’t know the intricacies of Canadian law, industry, lobbying groups. I hardly know where one would start to fix this mess. What I do know is that even in my own brief life-time I’ve seen my country become unrecognizable, in a blink of an eye. I have no attachments to this place, no loyalty. I doubt I am alone in these sentiments. I know that the political elite suffers from bad conscience and has decided to punish the rest of the country out of self-hatred. If you want my honest advice, leave. We are already Yugoslavia, in terms of racial distributions at least. As economic conditions deteriorate, ethnic groups will faction. I foresee a rise in casual violence. The best voting is done with your feet. Only Exit can force a government to dramatically change its course.

Generations are on their way of being locked out of secure employment and home ownership. This will only further undermine social cohesion, deepen regional divides, and sap national prosperity for decades to come. The choice is stark: confront these structural realities now, or accept a future of permanent precarity and declining living standards, ultimately turning Canada into a Third World Country.

Harold A. Innis, The Fur Trade in Canada, 1930.

Debates over whether Canada has ‘escaped’ the staples model remain, but this report focuses on enduring structural legacies rather than adjudicating that question. See Paul Kellogg, Escape from the Staple Trap, 2015.

Patrick Malcolmson et al., The Canadian Regime, 7th ed., 2021

Robert Bothwell, The Penguin History of Canada, 2007

Much more could be said about the historical roots of this crisis. Out of necessity I have been as brief as possible.

Stephen Poloz, The Next Age of Uncertainty, 2022

Statistics Canada, “Gross Domestic Product, Income and Expenditure, First Quarter 2025”, 2025. Most of the figures in the following section can be found here : Statistics Canada

Statistics Canada, “Labour Force Survey, May 2025,”, 2025. Most of the figures in the following section can be found here : Statistics Canada

Martine August, “The Financialization of Housing in Canada: Project Summary Report”, 2022

Denise Hearn and Vass Bednar, The Big Fix: How Companies Capture Markets and Harm Canadians, 2024

Ibid.

Andrew Jackson and Mark P. Thomas, Work and Labour in Canada: Critical Issues, 3rd ed., 2017

Youthful Cities, “The education-to-work gap: Why youth are struggling & how we can fix it,” 2025. Youthful Cities

C.D. Howe Institute, “2024 Labour Market Review: Challenges, Trends, and Policy Solutions for Canada,” March 2025. CDHOWE

Steve Pomeroy, “Hitting the reset button on the national housing strategy,” Policy Options, March 9, 2023. Policy Options

very well done article

One thing i would like to add is that lack of a stable social security system such as the US via 401ks, it seems to me that the financialization of real estate was of great benefit to the incumbent boomers and placated much of their negative sentiment. The immense protections on real estate and their market value would make affordablity political sucide in metropolitans. We’re ultimately a socialist country with regards to protections of markets and controlled supply of houses and staples. Very well researched and thought out article, your logic flows nicely.